* * *

On a cheerier note, been reading up on various terms currently popular

in philosophical discourse.

https://www.lefigaro.fr/langue-francaise/quiz-francais/aurez-vous-un-sans-faute-a-ce-test-sur-le-vocabulaire-de-la-philosophie-20200627

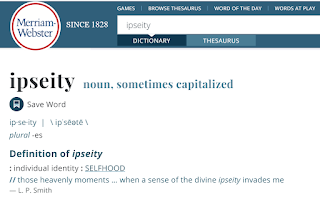

Below, looking for ipsity (ipseity).

Article: Ipsity in l'Encyclopédie philosophique.fr

author: Jérome Dôkic, EHESS

translation: GooleTransalte/doxa-louise

Introduction

The etymology of the word "ipseity" suggests the reference to a thing considered as such, or in itself, but contemporary philosophy usually reserves the use for the human person. In this regard, the notion of ipseity is transversal, and concerns several fields of philosophy, including metaphysics, philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. On the metaphysical level, the question concerns personal identity, or what makes that a person is or remains the same, at a given time or over time. One may wonder, for example, whether personal identity differs from the identity of other genera or species of entity, animated or not. For the philosophy of the mind, ipseity refers to the psychological relationship, supposedly privileged, that a person maintains with regard to himself. The question of selfhood is then that of self-awareness, or the various forms in which a person represents or experiences himself. As for the philosophy of language, it uses the notion of ipseity in particular to designate the reflexive forms that language authorizes or imposes, for example the difference that there may be between the formula "Marie saw her reflection in the mirror" and the formula "Maris saw herself in the mirror" which, unlike the first formula, implies that Mary recognized herself in the mirror.

As often happens in philosophy, each area has claimed its theoretical and methodological priority over the other areas. Some metaphysicians consider that the question of personal identity is first in the order of explanation, and that self-awareness can only be understood from a theory independent of what makes a person be or remain identical to itself. On the contrary, a philosopher of the mind can argue that the sense of selfhood must be the starting point for an analysis of selfhood, and that metaphysical questions are secondary, or dependent on psychological questions. For example, John Locke suggested that awareness a subject has of a part of his body "from within" (as a part of itself) is that it is a part of himself (2002, Book II, Ch. 27, Section II): self-awareness determines the ontology of the self. More recently in the history of philosophy, philosophers of language, often inspired by Ludwig Wittgenstein, have denounced the puzzles related to selfhood as illusions of language (or "grammatical" illusions), and considered that a careful analysis of the use of certain verbs and pronouns could be enough to allay most of the philosophical concerns linked to personal identity or self-awareness.

In the history of philosophy, the question of self-awareness has been associated with the knowledge of what we are, that is to say the type of entity to which we belong. This is how René Descartes allowed himself to draw from Cogito , conceived as the quintessential form of self-awareness ("I think, therefore I am"), the conclusion that the subject is not identical to any material body, not even his own (cf. for example Descartes' answers to Pierre Gassendi in the Responses to the fifth objections which follow the Metaphysical Meditations ). Conversely, in the Critique of pure reason, Emmanuel Kant will seek to radically dissociate self-awareness from knowledge of what we really are, by concluding that the nature of the self is unknowable (cf. B158). The relationship between selfhood as self-awareness and knowledge of our own nature is a notoriously complex subject. Today, we cannot approach it without a substantial conception of selfhood and the articulation between the three levels of analysis (linguistic, conceptual and perceptual) which have just been distinguished.

...

* * *

Published on 7/21/2017 | Le Point.fr

author: Sophie-Jahn Arrien, Laval University

translation: Google Translate/doxa-louise

Ricœur and narrative identity

Who is this "I"? In "Temps et récit", the philosopher evokes an evolving entity that transforms itself through the weaving of tales. Critical analysis of a text.

Paul Ricœur (1913-2005) analyzes in many of his texts the great detour that the subject must undertake to return to itself. With this approach, a subject is brought to light which represents more a point of arrival for the philosophical effort than its point of departure. But who is the subject if it is not a purely formal truth? Who is he who finds himself by understanding and interpreting himself? Who am I, that I who says "I"?

To this question, we respond spontaneously by highlighting our character traits, our ways of being, in short, what remains fixed and identifies us as being the same person despite many changes. This form of identity has its limits. Because, strictly speaking, the permanence in time of what I am does not allow us to answer the question "who am I?" ", but rather" what am I? " Ricœur, to counter this shift, proposes to distinguish two types of identity: the first in the sense of idem or "sameness" (idem means "the same" in Latin), and the other rooted in ipse or of oneself (one will then speak of “ipseity”). The same identity applies to any object that remains in time. But if the subject does not simply exist like a chair or a stone, its identity cannot be reduced to that sameness. Rather, it refers to the dimension of selfhood which manifests itself concretely by the voluntary maintenance of self in front of others, by the way in which a person behaves such that "others can count on him". That which illustrates for Ricœur the emblematic figure of the promise in which I first commit who I am and not what I am (it is precisely beyond what I am today that I commit to keep my word).

The two ends of a chain

Ipsity does not, however, substitute for the sameness of the subject, but completes it. And this is where narrative identity comes in, that is to say that which deploys the dialectical relation uniting the poles of the idem and the ipse. This notion, which appears for the first time in Ricœur in the conclusion of Temps et récit(Seuil, 1983-1985), is based on the idea that each individual appropriates, or even constitutes himself, in a constantly renewed narrative of himself. It is not an objective story, but one that, as a writer and reader of my own life, "I" tell about myself. Personal identity is thus formed through the narratives it produces and those it continuously integrates. By doing so, far from freezing in a hard core, the “I” is transformed through its own stories but also through those which are transmitted by tradition or literature which are grafted onto it, never ceasing to restructure the whole of personal history.

"By depictins as a narrative the aim of real life, it gives it the recognizable features of characters loved or respected," writes Ricœur in Soi-même comme autre (Seuil, 1990). The narrative identity brings the two ends of the chain together: the permanence of character over time and the subsistence”. But because it allows several stories as well as their permanent restructuring, it is therefore never perfectly finalized, and because of this, it enriches the ordinary understanding of a person thus conceived of as a character engaged in a narrative struggle against the scattering of lived experiences.

Starting from the notion of ipseity, Ricœur thus leads us to a flexible and dynamic iconcept of dentity which immunizes against the danger of a return, even indirect, towards a "strong" self understood as a hard core. Often used by literary studies, Ricœur's analysis also allows dialogue with political philosophy, in particular that of the Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor who recognizes the interpretative and historical horizon within which the "self" takes source.

* * *

No comments:

Post a Comment